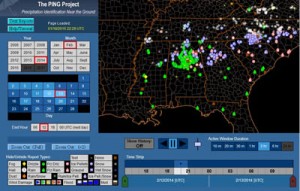

Screen capture of the mPING webpage. Everything a potential participant needs to know is available on this single page.

Screen capture of the mPING webpage. Everything a potential participant needs to know is available on this single page.

Are raindrops falling on your head? Is your car getting pelted with hail? Is snow glistening in your treetops? mPING is collecting your weather reports to improve forecast accuracy.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is gathering weather data from all over the world to help meteorologists at the National Severe Storms Laboratory develop weather-predicting algorithms. The work of mPING volunteers will help create a new database of information about weather, which in turn will help meteorologists better predict future weather.

Download this case study (PDF, 96KB)

Website: mPING

Display of mPING reports over a 2-hour period centered on 1900 UTC for 13 February 2014. The legend is in the lower left-hand corner.

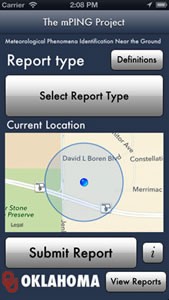

Volunteers select what type of precipitation they are observing at various times during the day using a mobile application. They can report on any of the following: rain, freezing rain, drizzle, freezing drizzle, snow, ice pellets, mixed rain, wind damage, tornadoes, flooding, landslides and reduced visibility such as fog or blowing dust or sand. Volunteers can also report “none” when there is no precipitation or when the precipitation has stopped, and they can select “test” to test the use of the app. The data are displayed on a real-time U.S. map.

Volunteers are encouraged to use a ruler to measure the size of hail from a thunderstorm and then report the data using the app. Scientists can compare volunteer reports from the field with what radar detects, using the data to develop new technologies to determine precipitation patterns and types.

View of the mPING app on an iPhone. The interface is kept very simple and straightforward.

Volunteers need a mobile device to participate. When the mPING app was launched, only 3 percent of volunteer observations came through a Web interface. Due to security concerns and the need to keep the Web form aligned with the mobile platform, the developers focused on the mobile apps, discontinuing the Web form. Not all mobile device platforms are supported by the mPING software.

If volunteers report on weather location when the mobile device has poor or no GPS reception, a slight discrepancy in data can result. Without good GPS reception, the location of the nearest cell tower is reported, which could be a few miles away from the user’s true location. Users are not allowed to override their GPS location and set their precise location.

Since its release in 2012, the mPING Project has received over 860,000 reports. The data are used to improve weather computer models, forecast ground icing for road maintenance and aviation operations, and predict the potential for in-flight icing. Many National Weather Service offices also display the data on large monitors and use the reports to fine-tune their forecasts.

So far, a direct consequence has been an update of the precipitation-type algorithm within the Rapid Refresh forecast model developed and maintained by the Earth Systems Research Laboratory. Results using mPING observations to verify forecast precipitation types showed that Rapid Refresh under-forecast the occurrence of ice pellets. After review, the laboratory found and corrected a typographical error in the code that produces precipitation forecasts.

The mPING case study illustrates the following steps in the Federal Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing Toolkit:

Lans Rothfusz

Email: lans.rothfusz@noaa.gov